More on:

This is a guest post by Aubrey Hruby and Jake Bright. They are the authors of The Next Africa: An Emerging Continent Becomes a Global Powerhouse.

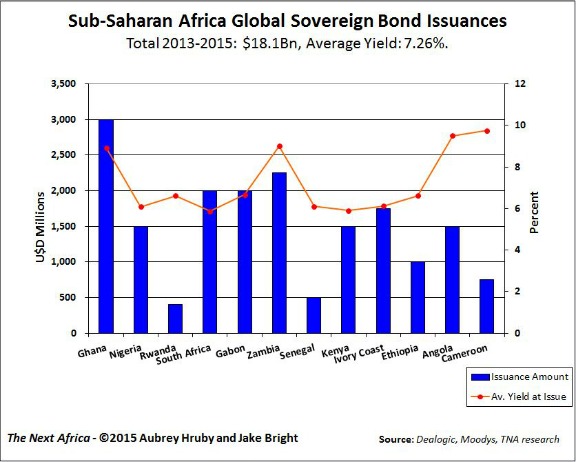

Sub-Saharan African governments are tapping global capital markets at a rapid pace, issuing $18.1bn in dollar denominated eurobonds from 2013-2015, nearly triple the $7.3bn issued in the previous three years.

While government bond markets rarely capture the allure of stocks, each year international investors purchase trillions of dollars in sovereign securities around the world. Whether U.S. Treasuries or Chinese 10-year bonds, these fixed-income instruments generally provide more stable (though typically lower) returns than stocks, while offering nations financing for services and infrastructure. Sovereign bonds also bring greater accountability to governments through national credit ratings and variable yields, both of which go up or down based on good or bad economic policies.

Historically, with the exception of South Africa, Africa has largely been a non-factor in sovereign bond markets. Few countries in sub-Saharan Africa even had sovereign credit ratings (a basic requisite for issuing national bonds) deep into the 2000s, reflecting the region’s past as one of the global economy’s most financially disconnected areas.

Africa’s recent boom in global bond issuances, many maiden, is changing this picture. Today, many national issuers are getting first time credit ratings from Moody’s and S&P, as they’ve become more accountable and transparent. African governments are also benefiting by inclusion in standard indicators, such as J.P. Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index Global (EMBIG).

Many Americans are already holding African bonds in their investment accounts. Institutional investors such as PIMCO and Fidelity have been increasingly buying them, attracted to higher yields, improved sovereign risk profiles, and a new regional asset class to diversify portfolios.

Connecting to global bond markets has given African governments, who are scrambling to deliver infrastructure, a source of financing other than private loans or foreign aid. Nigeria is funding greater electricity output with its recent $1.5 billion issuances. Zambia plans to spend on improved health care and railways. Ethiopia is using eurobond proceeds to finance a 6000 watt hydroelectric dam and industrial parks toward its goal of becoming an African manufacturing hub.

Inevitably, sub-Saharan Africa’s entry into global bond markets has its critics. Given the previous fiscal woes of African governments, it’s no surprise that some business journalists and economists have sounded alarms regarding SSA’s recent sovereign borrowing. They point to the possibility of a new African debt crisis or warn that bonds impose less conditionality and monitoring on governments than MDB financing.

There are certainly always risks to sovereign debt markets (see Argentina). But the critics of Africa’s new global bonds have yet to suggest better ways for governments to pay for crucial infrastructure. To graduate from “frontier” to “emerging” market status sub-Saharan African nations need sovereign bonds, just as China or Brazil did. When African governments meet the same criteria as other countries to receive national credit ratings, list on benchmark indexes, and pass the scrutiny of the world’s leading investment funds, why shouldn’t they finance their development through international bonds? If certain governments, through poor fiscal and economic management, bring on the scrutiny of ratings agencies and investors, that reflects a greater degree of financial accountability.

Sovereign credit ratings and variable bond yields provide instant and economically tangible feedback. Investors and Africa’s citizens will be watching keenly how these new bond funds are spent compared to original commitments. Too much corruption or bad economic policy will cause investors to dump certain bonds and drive up borrowing costs. The Nigerian government realized this during its 2014 central bank whistleblower scandal. When globally respected central bank governor Lamido Sanusi raised the issue of $20bn in missing state oil revenue to Nigeria’s parliament he was fired by then president, Goodluck Jonathan. The move sparked widening spreads on Nigeria’s new bonds, a drop in its stock market and currency, and a Standard & Poor’s sovereign credit downgrade.

As sub-Saharan African governments further normalize their economies to global capital markets, investors can certainly expect more sovereign bond issuances. Americans will also be more likely to see African country names in the fixed income allocations of their 401k’s.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store